Trigger Warning: Graphic depictions of abuse and non-consensual sexual acts

An official selection for the Un Certain Regard competition at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival, Pleasure Factory depicts three different stories that take place throughout the same night at Singapore’s infamous red light district Geylang.

Whether it’s a young NS man looking to lose his virginity, a painful moral dilemma of an older sex worker inducting her young daughter into the industry, or a jaded service provider trying to look for some reprieve from her sex work – viewers can journey through various snapshots of how life can be like at Geylang.

The movie is filmed in a way that makes the daily happenings at Geylang seem mundane and organic – the camera follows around the characters shakily, dialogues are kept to the minimum, awkward silences replace the usual background musics in a film, the actors were even acquainted with each other and with their story lines just right before the actual shoot. One would not even know the names of some of the film’s characters until midway through the movie. This creates the impression that the red light district and sex work industry is just yet another nameless, mundane place and community in Singapore. Some central themes about sex work can also be drawn out from the film.

Inherent Stereotypes about the Industry

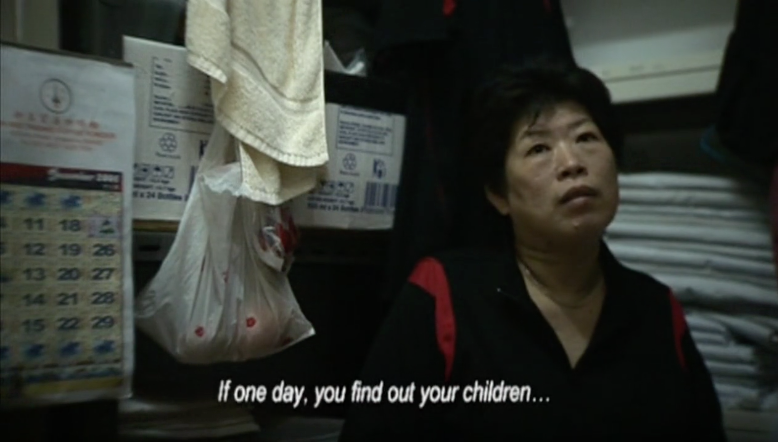

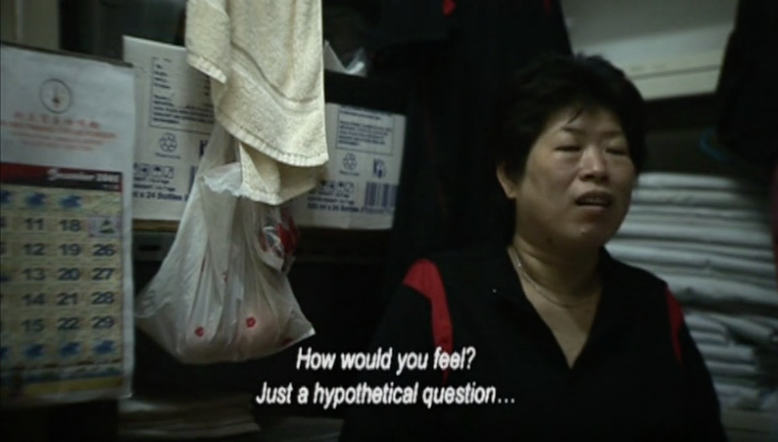

Dialogues between the characters and two short documentary-style interviews slotted into the film reveal stereotypes that locals might have towards the industry at that point in time (and even now).

Dilemma between Morality and Livelihoods

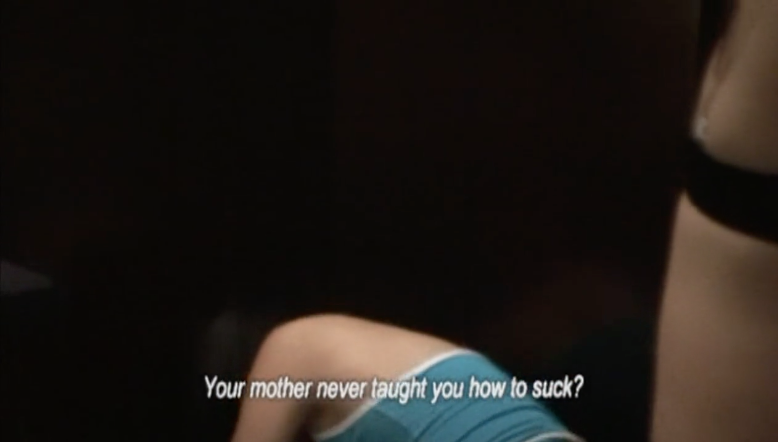

In the film, an older sex worker (as portrayed by acting veteran Yang Kuei-Mei) was forced into a moral dilemma: Is it worth it to introduce her own daughter into the sex work industry for the sake of earning for a livelihood? Viewers would no doubt feel pained and sympathy for the conflicted, and also disturbed at the older man’s interest in having a young girl provide oral sex to him.

The juxtaposition of the actual visual of the man forcing the girl into giving him a blowjob and the image of the troubled mother smoking with trembling hands would also leave viewers feeling haunted by the fact that this can actually be the harsh reality for some.

A Shared Space for Unmasking and Vulnerabilities

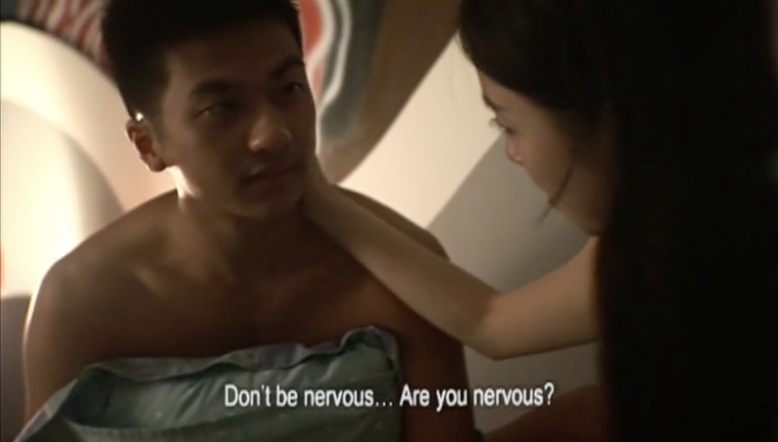

Interestingly, the session between the sex workers and their clients can also be emotionally intimate. The army boy trying and failing to hide his apprehension and awkwardness of losing his virginity, the sex worker revealing her hardship of working in the industry to support her family in China which left the NS boy in tears, the tired service provider bringing a busker home just to feel a semblance of quiet intimacy and reprieve with him without sex in the equation – amidst all the hustle and bustle of Geylang and behind the closed doors of the four walls, these characters bared the vulnerable sides of themselves that they might not even share with their friends and families. This also further cements the idea that sex work is care work.

Food for Thought

The film does not necessarily shove overt ‘morals of the story’ into the audiences’ faces, but a closer look at the portrayal of sex work and sex workers reinforcesthat sex workers are in the industry only because they have no other choice (e.g. having to support one’s family), and that sex work is pitiable. This portrayal takes away the agency that sex workers have by reducing them to people who require ‘saving’. The director of the film himself, claimed that people would not be able to find “true pleasure” in red light districts as pleasure is very transient, and that the “pleasure” that characters in the film experienced was forced and fleeting. When in reality, sex work can be a choice and it can be pleasurable.

In this vein, Pleasure Factory’s portrayal of sex workers is reminiscent of the 2022 local film Geylang’s portrayal of sex workers, which reflects the stereotypical misconception that sex workers are miserable and helpless. Considering the fact that Pleasure Factory and Geylang were produced with a 15 years gap between them, what does this then say about Singapore’s unchanging view towards sex workers?