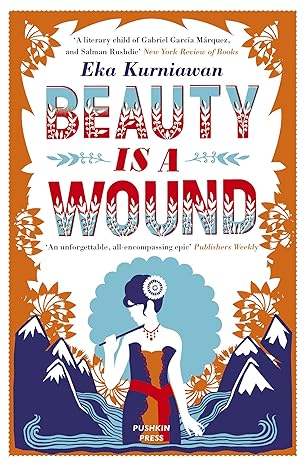

Synopsis

Penned by Indonesian writer and screenwriter Eka Kurniawan, Beauty is a Wound (2002) centres around the life of half Dutch half Indonesian sex worker Dewi Ayu and her descendants in the fictional town of Halimunda. Kurniawan combines folklore, wit and graphic imagery to spin a captivating tale of Indonesia’s history, drawing significant parallels between the violating nature of colonialism and rape.

The book takes readers through various time periods to trace the lives of Dewi Ayu and her daughters, Alamanda, Adinda, Maya, and Beauty, and their struggles in the backdrop of colonial and Japanese occupation of the land. Kuniawan’s stunning world building immerses you in the lives of his characters, and the supernatural forces which drive the family’s history makes for a hard to put down read.

Beauty is a Wound expertly navigates poignant themes like class, love, and gender, and doesn’t shy away from graphic descriptions of rape, beastiality and the realities sex workers face with a satirically humourous tone that lightens the mood without taking away from the gravity of the situation.

While this book may not be for everyone, it’s still worth thinking about how its themes speak to us as allies and sexy workers!

How do we exercise agency when the odds are stacked against us?

Throughout the narrative of Beauty is a Wound, women turn to sex work as a means of survival, taking their lives into their own hands no matter what life throws at them.

This is most apparent in the life of Dewi Ayu, who was taken prisoner during the Japanese occupation. While she was in the camp, she offered to sleep with the commandant so he would agree to get medical aid for a dying woman.

When she was forced to become a comfort woman for Japanese soldiers alongside other Dutch women, Dewi Ayu shared how she coped with their traumatising situation.

“Try to find one guy out of all of them who you like a little, and service him with your full attention, and make him addicted to you so that he will come back to you every evening and pay you for the entire night. Servicing the same person over and over is way better than sleeping with lots of different men”.

After the war, Dewi Ayu continued with sex work to provide a better life for her three daughters, sending them to the best schools and taking care of them during the day “just like any regular mom”.

Dewi Ayu is not unique in her display of tenacity and agency amidst trying circumstances. For many sex workers, their work is an empowering display of their resourcefulness, and how they find ways to support themselves and their families. In the face of oppression, discrimination, and limited opportunities, sex workers redefine their circumstances to create a better future for themselves and their loved ones on their own terms.

Is there more to love as we understand it?

It’s a common notion that “true” love only exists in the context of marriage, and that relationships with a sex worker are loveless, transactional affairs.

Beauty is a Wound is quick to flip these ideas on their heads, shattering the image of marriage being void of any transactional motive, as well as suggesting that sex work can, in fact, be a way of preserving love, rather than destroying it.

“Really every woman is a whore, because even the most proper wife sells herself for a proper dowry and a shopping allowance,”

“‘If a man goes to see prostitutes, it means that he doesn’t have to take a concubine. Every time a man takes a concubine he’s probably breaking the heart of that concubine’s beloved. So a love is destroyed and lives are torn apart. But if he visits a prostitute, he only hurts a wife, who is clearly already married and who clearly has already done something wrong to make her husband go to a whorehouse in the first place.”

Beauty is a Wound conveys the irony that while marriage is thought to be the embodiment of a loving relationship, it’s usually between married couples in the book that the most abuse takes place, whereas Dewi Ayu’s clients often “treated her better than they treated their own wives”.

Perhaps it’s worth rethinking our inherent understanding of the contexts in which love can and cannot exist.

Can we define our worth beyond what society says of us?

It’s an unfortunate reality that sex workers are often scrutinised and discriminated against purely because of their jobs. But isn’t there more to a person than their line of work?

The residents of Halimunda reflect the attitudes that mainstream society holds towards sex workers, referring to them as “whores” or “prostitutes”, and even putting them on the same level as thieves, crazy killers, and communists. These attitudes went on to affect the way Dewi Ayu’s children were viewed by the villagers.

“People would say that a depraved family would forever give birth to children just as depraved.”

Nevertheless, Kurniawan goes to great lengths to humanise Dewi Ayu, creating depth to her character that goes beyond a despised sex worker.

At first, we as readers are led to believe that Dewi Ayu cared little for her children, referring to her daughters as “demon children” and attempting to kill her youngest daughter.

“I already did everything I did to try to kill you. I should have swallowed a grenade and detonated it inside my stomach. Oh wretched little one – just like evildoers, the wretched don’t die easy”.

But by the end of the book, we learn there’s more to Dewi Ayu’s supposed hatred than meets the eye. I won’t say much for the sake of spoilers, but it was a revelation that truly revealed the depth of her character.

As readers, we only reach this point after the process of journeying with Dewi Ayu, hearing her story and learning about who she was beyond what society thought of her. Likewise, we only learn more about the people around us when we make space to get to know them for who they are, rather than making broad assumptions based on surface-level observations.

Why shouldn’t we also extend this grace to sex workers, who have as many dreams, hopes and hurts as anyone else?

Conclusion

One of Beauty is a Wound’s greatest strengths is that sex work isn’t the main focus of its story. Kurniawan doesn’t go out of his way to sensationalise or gratify sex work, but incorporates it as a way of portraying the depth of his charaters and the world they inhabit, and makes it part of a wider commentary on themes such as love and oppression.

Even so, there is still much which we can learn about and understand about sex work and the people in the industry through this compelling novel. Narratives that broaden our perspectives on how we see agency, value, and love give us the opportunity to work towards creating a society where sex workers are given the respect and compassion they deserve.